Coal mining truck in the region of Cerrejon – coal mining causes disproportionate damage to the environment in Colombia. Credits: Troskiller, CC BY-NC 2.0

La Mesa has conducted a sustained and democratic coalitional process, which is pluralistic, multi-ethnic, intersectoral and ideologically diverse. As a coalition, its story could be told from many perspectives. This article centers on the trade union movement perspective and looks at how the Colombian energy sector unions, particularly the oil workers’ union, engages with its coalition partners in a process of democratic deliberation to amplify common demands and overcome shared struggles.

La Mesa has had successes and faced challenges as it works to build a shared vision of an alternative development model. As Colombia’s first-ever leftist government takes over in August 2022, it will need to address many of the tensions that La Mesa has experienced, now at a national scale. Likewise, as Latin America finds itself amidst a new period of progressive and center-of-left governments in power, the region faces new opportunities, informed by past governing experiences, to reposition their political programs’ relationship to extractivism, land rights, energy poverty, and climate justice. Towards this end, La Mesa offers valuable reflections.

Oil workers address energy injustice

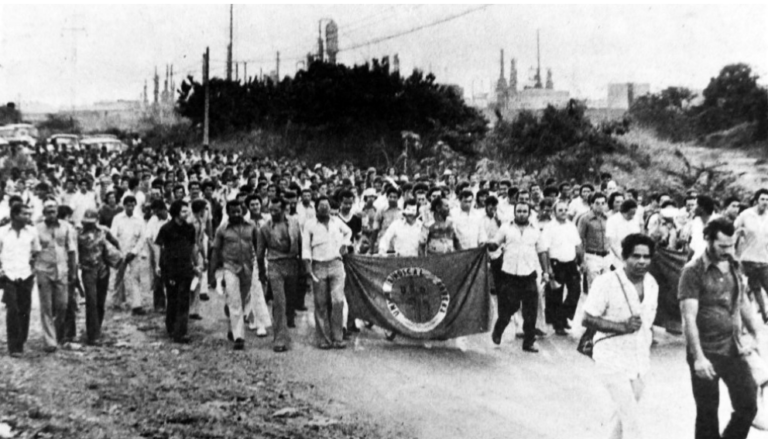

Since the mid-1980s, Colombia has infamously and consistently ranked as one of the most dangerous countries to be a trade unionist.[1] The Escuela Nacional Sindical, documented between 1971 and 2021, 15.317 violations against trade unionists including 3,295 homicides, 434 attacks, 253 forced disappearances, 7,624 death threats and 1,952 forced displacements. Paramilitary actors upholding upholding business interests were the main perpetrators.[2] Recognizing that only a broad coalition could provide sufficient power and attention to stop the violence, in August 1996 the Oil Workers Union (Union Sindical Obrera, or USO) organized the first National Assembly for Peace, with the slogan ‘So that Colombia May Live: Oil, Peace, and Progress’.

The assembly had a two-part objective: (1) to draw attention to the generalized violence that had been increasingly directed at organized trade unionists and the communities in regions where extractivist projects were based, and (2) to bring together affected groups to discuss the diverse impacts of extractivism on communities, ways of creating peace by socializing the benefits of the resource wealth, and to propose alternative models of development. The Assembly was one of the first seeds of what would later become Colombia’s leading coalition on energy democracy and just transitions.

Between 1996 and 2015, Colombia’s internal conflict and the violence against social leaders, including trade unionists, continued. When the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) announced they were holding negotiations with the Santos government, social movements across the country reflected on how they could play a role in the construction of peace with social justice (in opposition to the popularly referenced neoliberal peace for investors’ who perceived the conflict as a threat to their extractivist projects). In 2014, among the unfolding conflict, USO decided to open a series of democratic spaces to listen and systematically record the concerns, demands, and voices of social movements and community members in the lands where oil or other forms of extractivism operated. The trade union organized 13 regional assemblies and 53 sub-regional assemblies, in which more than 10,000 people and 1,800 social organizations participated. The central question posed to communities was how extractivism affected them, and what a different energy model – one that reflected the needs and desires of those most affected – could look like. To this end, USO understood the concerns, demands, and proposals from the assemblies were presented at the Second National Assembly for Peace in 2015.

The Second Assembly’s two most significant achievements were (1) the synthesizing of 850 proposals on energy democracy, and further consolidating these into 16 primary demands, and (2) the creation of a body tasked with continuing the process of discussion and alternatives-building across different sectors of society. The body became the Roundtable of Social Affairs, Mining and Energy for Peace (Mesa Social Minero Energética por la Paz – MSMEA, or La Mesa for short). La Mesa was premised on the belief that only a coalition could build an alternative to the prevailing extractivist model. According to one of the new coalition’s founding documents, its objective was to

‘Transcend from a scenario of dialogue and reflection to a scenario of significant impact on the public agenda of the energy mining sector, requiring the articulation between civil society platforms that share the commitment to an inclusive energy mining sector, and are committed to integral human development, equity, socio-environmental preservation and peace in Colombia’.[3]

Since its founding in 1922, the Oil Workers Union (USO) has organized strikes and assemblies with workers and communities to transform the national energy model and draw attention to the generalized violence directed primarily by paramilitary groups at organized trade unionists and the communities in regions where extractivist projects are based. Credits: Corporación Aury Sara

A diverse movement of movements

More than 100 organizations are formally part of La Mesa. They cover at least 15 sectors of society, including rural, indigenous, and black communities, LQBTQ and feminist organizations, workers, and student/youth collectives. Among the most active trade unions, other than USO, are Sintracarbon (coal), Sintraelecol (electricity), and FENSUAGRO (agriculture) and the most active social movements include Movimiento Ríos Vivos (Living Rivers Movement), Censat Agua Viva (Censat Living Water), and Mujeres Fuerza Wayuu (Wayuu Women’s Strength).

Due to the historic relation between land, gender, and anti-racism struggles, many of these movements are rooted in the leadership of Black and Indigenous women. For example, Mujeres Fuerza Wayuú was founded in 2006 to fight back against the transnational coal mining corporations which were damming and contaminating rivers, contributing to the ongoing water crisis in the Caribbean department of La Guajira. Despite receiving death threats from paramilitary forces working in conjunction with the coal companies, the women of Mujeres Fuerza Wayuú continue to organize to hold the corporations accountable.

Organization Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu – the group that fights for protecting the village of Wayuu and the earth. Credits: IPES Área Internaciona y Aula DDHH, CC BY-ND 2.0

There are genuine divergences and different interests between the members of the coalition. For example, communities had deep and historic grievances against the workers that operated on their land, especially as many of the workers were not local. Meanwhile, many workers are rightly proud of their contribution to the electrification of the economy and their militant legacy of social movement unionism.

‘Red’ versus ‘Green’ – or shared interests?

Following the commodities boom between 2003 and 2013,[4] extractivism has been framed as necessary for Colombia’s national development. It was even framed as a means of financing the 2016 Peace Agreements.

Participants in La Mesa have varied relationships with central questions of land and development, with some advocating for zero extractivism while others support zero expansion of the extractivist projects, and yet others differ on what kind of extractivism to propose. Within an economy that pitches extractivism-sector workers against social movements, and in a social context of conflicting interests, the coalition has had to address the fundamental question of how to find common ground based on shared interests, through discussion, and how to create an alternative energy and mining model in which all parties’ interests are addressed and met.

In the local and regional assemblies, it became evident that the trade unions, social movements, and community members had common grievances regarding state violence related to control of land and an energy model bent towards maximizing profit from extraction of resources to large corporations. Workers faced workplace violence and persecution for organizing, while social movements and communities faced land dispossession, forced displacement, and targeted killings for organizing around land rights. In this sense, the traditional dichotomy between ‘green’ and ‘red’ (or environmental and labour movements) was navigated and common ground was found on which to build a shared platform.

A Glencore coal mine – The company now owns all the coal mines in the Cerrejon region in Colombia. Credits: Tanenhaus, CC BY 2.0

Bottom-up approach with central oversight

La Mesa describes itself as a ‘collective, sovereign, pluralistic and democratic space’, with a bottom-up approach to governance and consensus-based decision-making. It also has a formal structure at the national level, consisting of three bodies. The National Coordinating Body is tasked with designing public policies related to mining, energy, and environmental issues. The Operation Team, made up of nine national representatives, implements the decisions and guidelines of the National Coordinating Body and engages in high-level political dialogue with the government, corporations, and the international community. The Technical Secretariat organizes, systematizes, and executes the national and regional agendas and presents reports from the territories to the national bodies and vice versa. In practice, this structure operates far more organically, depending primarily on the availability and participation of the members.

La Mesa’s members and leadership hold regular meetings (ranging from quarterly to biannually) to discuss projects and national developments in energy politics. Members meet more regularly in their regional and sectoral projects. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were efforts to hold meetings in locations other than the capital city of Bogotá.

The decision-making process strives to be consensus-based, meaning that when a divisive disagreement occurs (defined as when there is no overwhelming majority) members are asked to pause, collect further research and return to present their case with additional information. If a decision is still not reached, the topic does not become a common ground demand. Although this process does not always work perfectly, particularly when certain members hold strong positions, it is held to be the best approach. La Mesa has also lent support to member organizations when debates around extraction and energy democracy have sparked tensions within their structures.

Decisions are publicized through public-facing workshops, seminars, national meetings, statements, and books, such as one published by La Mesa on strategies for strengthening popular consultation.

Fracking: overcoming polarized positions

The debates around fracking are an example of how USO and La Mesa sought to find common ground on a divisive issue.

Fracking has been a controversial topic in Colombia since at least 2014, when the Ministry of Mines and Energy approved the practice, pending environmental reviews. Communities and trade unions had polemic debates about fracking.

Within the USO, the divide was heated, with some members arguing that the industry was suffering from job cuts and wanting to reactivate fracking to ‘save’ their company from the threat of increased privatization. A sector within USO proposed small-scale ‘pilots’ to test the practice. Meanwhile, a large sector of workers rejected fracking, citing the environmental and public health risks, arguing that no number of jobs could justify what they argued was a betrayal of the local communities. This debate made it into La Mesa, where an absolute majority of the social and environmental movements were against fracking. They supported the anti-fracking section of USO by facilitating local workshops to educate workers and community members across the country about the risks of fracking. In 2019, as a result of these and other efforts, the USO voted against fracking and in favour of pressuring the pro-fracking Duque administration to return the former national oil company, Ecopetrol, to 100% state ownership and to transition it into a renewables-based company.

Imagining what energy democracy looks like

Within the 16 agreed priorities distilled from the Second National Assembly for Peace, three themes are particularly important: ownership models, the democratization of benefits, and mechanisms for community control. These points reflect a nuanced understanding of energy democracy, beyond the usual dichotomy of ‘community versus state’.

Regarding ownership, La Mesa’s vision is one of co-existing and overlapping ownership models that respond to the specificities of local contexts while simultaneously advocating for an overarching public ownership model that (1) recognizes the state’s obligation to guarantee energy as a human right, while (2) reclaiming institutional capacity for long-term planning oriented towards the public good, and (3) replacing pressures of global neoliberal policy to deliver energy for profit and by private actors. At the same time, there is an understanding that merely ‘statist’ approaches to energy are insufficient and that a deep democratization of public planning, ownership, and governance must ensure community and worker control over any new energy model if it is to be just. Arguably, this nuance is due precisely to La Mesa’s diverse composition of social movements, trade unions, and national organizations.

One of La Mesa’s recommendations was for the creation of a national public company in each of the main energy sectors: mining, fossil fuels, water, and electricity.

For the mining sector, La Mesa proposes the creation of a commission, with delegates from trade unions, small- and medium-scale artisanal miners, and mining communities, to draft a reform of the Mining Code. This reform would ‘be based on respect for the environment and the health of miners and communities; it should clearly establish the fiscal and tax rules for the sector and focus on the constitution of a state-owned company to directly influence the planning and execution of the nation’s mining policies’.

For the fossil fuel sector, one proposal is to pressure for a decree for Ecopetrol – formerly the national oil company, now part privately owned – to return to being 100% state owned. This would give it leverage for influencing the planning and execution of the nation’s hydrocarbon policy.

With regards to water, Point 7 demands that the State recognize communities’ right to collectively manage water through community aqueducts and irrigation districts. In direct opposition to privatization efforts, La Mesa insists on public investment to strengthen and maintain the infrastructure of existing state and community aqueducts. In order to guarantee water (including the vital minimum) as a fundamental right for all, La Mesa calls on the prohibition of all service cuts and, on a larger scale, the prohibition of mining activities to operate near ecosystems deemed critical to the water cycle. To legislate these and other water management needs, La Mesa proposes a Water Reform that compliments and coordinates with the Agrarian reform.

In terms of electricity, La Mesa proposes strengthening the departmental (a mid-level scale similar to States in the US) electric energy companies and to initiate the creation of a country-wide state-owned electric energy company. This company would directly influence the sector’s policies throughout the production chain.

While public ownership is a long-term goal, in the shorter term La Mesa proposes mechanisms for democratizing the benefits of the energy sector. For example, La Mesa advocates for the elimination of the Mining Code’s denomination of mining as an activity of ‘public utility and social interest’. In a country where corporations hold substantial influence over the state, this denomination creates an opening for legal interpretations that privilege corporate interests over public and environmental ones.

Several other proposals aim to democratize extractivism by distributing the benefits and orienting extraction towards meeting local needs. For example, La Mesa recommends reforming the tax benefits awarded to companies in the mining-energy sector, installing mechanisms to prevent the manipulation of transfer prices, and reviewing the royalties scheme and its tax deductions in order to increase the state’s share of the wealth generated by extractivism. The reclaimed income would create a Fund prioritizing investment in public education and health as well as industry and research to develop publicly owned technology for just transitions. La Mesa also proposes the creation of a second special Energy Fund for technical and scientific research towards decentralized, autonomous, and community energy projects.

The Ecopetrol refinery in Barrancabermeja, Santander, is Colombia’s largest refinery. Its modernization has long been a demand by USO. Credits: Aris Gionis, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Guarantees for community sovereignty

La Mesa also recognizes and encourages other measures for alternate forms of community control, participation, and sovereignty. These include a demand for guarantees that municipal autonomy regarding mining and other extractive activities be respected. A second demand is to practice free, prior, and informed consent on the terms of the Indigenous, racialized, and peasant communities, with particular rigour within the framework of the export-oriented ‘projects of national and strategic interest’ (known as PINES).

Water rights are highly contested between the interests of local communities and private extractive interests; in response, La Mesa calls for the ‘recognition and enforcement of the right of communities and organized populations to collectively manage water through community aqueducts and irrigation districts’. They are also calling for an immediate end to the privatization of water and propose that water management ‘should be exclusively in the hands of the State or organized communities’.

Coal mining. Credits: AveLardo, CC BY-NC 2.0

Big ambitions, but challenges remain

La Mesa is a valuable case study, both for its notable achievements and its significant shortcomings and challenges.

The central questions it is trying to address are ambitious and go to the heart of how current energy and economic models must be fundamentally reformed:

What common demands address our diverse and shared grievances? How do we transition from common demands to a shared construction of an alternative energy model? Short of transforming the entire model, what reforms and public policies reflect our common demands? In a world increasingly saturated with one-off events, these are substantive questions for which consistent, frequent, and sustained discussion is necessary. La Mesa members understand that decisions on divisive topics cannot be rushed or imposed because doing so would jeopardize the trust of the coalition. Yet this sustained discussion is a constant challenge to maintain. Participation ebbs and flows, with the most consistent participants being those in Bogotá or other major urban centres. Maintaining engagement with more localized processes in rural areas is difficult and the COVID-19 pandemic made it more so: virtual meetings have excluded members without access to reliable Internet.

Furthermore, anti-capitalist organizations are not immune to internally replicating the racist, classist, and sexist society in which they fight, and this holds true for the interpersonal dynamics of La Mesa. For example, while women make up a significant sector of the social movement participants in La Mesa, they are hardly represented among labour union delegates, and not one of the 16 proposals includes an explicit demand for gender justice. On the other hand, a disproportionate share of social leaders murdered, disappeared, dispossessed and displaced by extractivist projects are from Black and Indigenous communities.

In context, the reference to “territorios” throughout the 16 proposals of La Mesa can be understood to include ethnic and racialized communities but only once, in Point 12, are ethnic communities explicitly mentioned (with regards to the guarantee to demand prior consultation for PINES projects). The program as a whole would be strengthened by incorporating a more comprehensive anti-racist lens that champions historic anti-racist and decolonial demands aimed at restorative justice (including the collective land restitution and redistribution as well as the demands incorporated into the Ethnic Chapter in the Final Peace Agreement). In her thesis, Ingrid Lizeth Lozada Jara reviews the petitions born from recent strikes and analyzes the material that alludes to Black communities, contributing to an analysis of how demands can more explicitly address the legacies of racism.

Developments

In January 2019, La Mesa convoked a national meeting in Bogotá with 300 social leaders from its participating movements, including USO and CUT Colombia, and invited members of the progressive “alternative congressional bench” many of who continue to hold positions in the newly inaugurated 2022-2026 Congress. Among other points, the participants reiterated the demand for a publicly-owned Ecopetrol to help lead the Just Transition and renewed their collective efforts to oppose its privatization.

A social movement activist in the heart of government offers hope

The election to government of one of the most powerful social movement leaders in the mining sector gives grounds for hope. Francia Márquez is a Black feminist, lawyer, defender and artisanal miner.[5] Before entering electoral politics, Márquez was among the 80 majority-Black women who marched 350 kilometres to Bogotá to protest against large-scale mining on their land at La Toma. Their campaign ultimately resulted in the successful removal of illegal miners and their equipment from the community. Márquez’s leadership has instigated a country-wide public debate about the social and environmental injustices around large-scale mining.

On 7 August 2022, Francia Márquez will be inaugurated vice-president of Colombia, with Gustavo Petro as president. The historic significance of this election cannot be overstated: it is the first time in its entire history that Colombia will have a leftist government. Petro and Márquez were elected as representatives of Pacto Histórico, a coalition of 20 left and centre-left parties. In the congressional elections in March 2022, Pacto Histórico saw 20 senators and 26 representatives elected, making it the largest political force in the Senate. Pacto Histórico’s environmental programme prioritizes transitioning Colombia ‘from a primary energy matrix, predominantly fossil fuels, economically dependent on coal and oil, to a diversified one, based on our renewable energy potential, (…) to face climate change and strengthen the country’s capacities for a productive economy’.

The next four years will require navigating many of the tensions that La Mesa has experienced at a national scale. The coalition’s experience is an important case to study in order to understand the power of such a coalitional process, and the challenges in maintaining it, and will continue to provide lessons for other coalitions in the Global South and beyond, who share its dream of a just and democratic energy transition.

Recommended Resources:

- Extractivismo y posconflicto en Colombia: retos para la paz territorial. Editores: Astrid Ulloa, Sergio Coronado (2016)

- Extractivismo: conflictos y resistencias, Coordinadoras Tatiana Roa Avendaño y Luisa María Navas

- “Las Consultas Populares: una estrategia legítima para la Defensa y el Cuidado de la vida, el agua y el territorio” Mesa Social Minero Energética por la Paz

- “Petróleo, paz inconclusa y nueva lógica del conflicto” (2018) Libardo Sarmiento Anzola. Agencia de Prensa Rural

- “21 Propuestas desde el sector minero energético para la paz y la transición hacia un proyecto compartido del país” (2019)

- Diálogo Regional por la defensa y cuidado de la vida y el territorio, Magdalena Medio (june 2018) Cumbre Agraria, Campesina, Étnica y Popular; Mesa Social Minero Energética por la Paz

- A conversation between Francia Márquez Mina and Angela Davis, September 7, 2021 https://pcp.gc.cuny.edu/2021/09/a-conversation-between-francia-marquez-mina-and-angela-davis/

About the authors

Lala Peñaranda is the Communications Coordinator for NY Renews and helps coordinate the Latin America work of Trade Unions for Energy Democracy (TUED). She is a member of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), Science for the People (SftP), and Internationalism from Below (IfB).

Isabel Peñaranda Currie is a PhD student in City and Regional Planning at the University of California – Berkeley, where she is researching the political economy of urban policies in Latin America, specifically relating to land markets and value and informal settlements. She is also host of “Sur-Urbano”, a podcast on Latin American cities.

Coordinator: Lavinia Steinfort

Reviewer: Tatiana Roa Avendaño

Copy editor: Sarah Finch

Translator: Mercedes Camps

[1] Democracy Now! (2018) ‘Afro-Colombian Activist Francia Márquez, 2018 Goldman Prize Winner, on Stopping Illegal Gold Mining’. https://www.democracynow.org/2018/5/18/afro_colombian_activist_francia_marquez_2018

[2] Ocampo, J. A. (2017), ‘Commodity-led Development in Latin America’, in G. Carbonnier, H. Campodónico and S. Tezanos Vázquez (eds.) Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, Leiden: BRILL. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76w3t.11

[3] Olaya, A., Pedraza, H. and Teherán, S, (2012) La violencia contra los movimientos sindicales vista desde el sector educación y salud. Bogotá: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung en Colombia. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kolumbien/09151.pdf

[4] A 20-minute documentary co-produced by the Escuela Nacional Sindical provides an overview of the history and violence of the trade union movement in Colombia. View El Sindicalismo Cuenta (2020) here: https://youtu.be/ICyhMiQWrDY

[5] Diálogo Regional, 2018.