Energy sovereignty – which is based on the highest level of democracy – means to listen to, give voice to, empower, meaningfully engage with, and encourage voting by the largest number of people possible. They must have the democratic power to decide what kind of energy model they want. In other words, how people want to source, own, organise and supply energy. For example, what kind of energy-related policies should be implemented by their public administration, energy enterprises and energy communities and how these entities can be fundamentally democratised. The aim is to maximise long-term social, environmental, economic, political and cultural benefits for all inhabitants of a territory, whilst also respecting the sovereignty and rights of people and nature elsewhere, including all human and non-human life.

Municipalism is a way to bring about energy democracy and can be seen as a transformative element in itself. It is made up of all those groups that are pushing hard for progressive social change at the municipal level, wherever they are located. Municipalism is not solely about the way in which local governments and councils act; the key element is the interaction between two spheres – local government and social movements. Firstly, it brings political decision-making closer to the people by giving citizens a greater ability to influence those decisions. Secondly, transforming the current energy model – which can be described as centralised, fossil fuel-based, oligopolistic, patriarchal, and socially and environmentally unjust – towards a redistributive, renewable, democratic, just and ecofeminist model, demands radically new forms of ownership and governance.

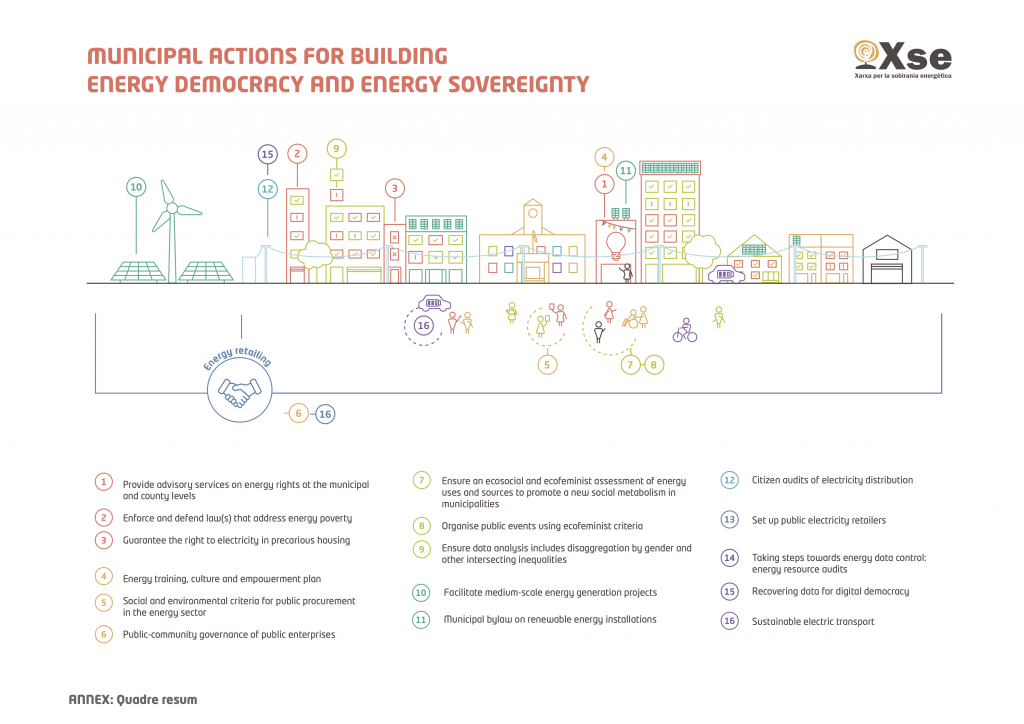

The Municipalist Manifesto proposes a profound change to the current energy model. It covers the following energy-related thematic areas: energy poverty, participation, transport, ecofeminism, generation, distribution, retailing and data ownership. Presented in the following are 16 proposals from these areas, applicable to different actors and levels.

Download the full manifesto here.

Energy Poverty | Proposal A.1: Provide advisory services on energy rights at the municipal and county levels

Set up advisory services relating to energy rights and energy supply issues at the municipal level (or county level in the case of small municipalities). Deal urgently with cases where people have been cut off due to non-payment; provide general advice on tariffs, discounts, contracted power and ways to save energy and optimise its use; arrange for contract changes and discounts from energy companies; and organise trainings and workshops about energy rights and how people can make their homes more energy efficient.

Energy Poverty | Proposal A.2: Enforce and defend law(s) that address energy poverty

To address threats to cut off power supply, the precautionary principle should be applied in terms of determining capacity to pay, together with energy poverty protection measures that are triggered on the basis of people’s income levels. These should be established by law. With regard to discounts, citizens will be provided with and advised to take advantage of a discounted social tariff designed to prevent increases in the tariff debt owed by families in vulnerable situations. It is essential for municipal and regional governments to present a united front to obtain signed agreements with energy suppliers to ensure that the latter absorb all the costs of measures to combat energy poverty.

Energy Poverty | Proposal A.3: Guarantee the right to electricity in precarious housing

Enable provisional contracting of electricity supply for individuals or families living in unoccupied buildings who are at risk of being made homeless.

Participation | Proposal B.4: Energy training, culture and empowerment plan

We propose that municipalities develop energy training, culture and empowerment plans. These should contain training resources designed for different audiences and social groups, and municipalities should make a particular effort to reach out to those groups who tend to be the worst affected by the current energy (and socio-economic) model but the least likely to participate in oversight of or discussions about it.

Participation | Proposal B.5: Social and environmental criteria for public procurement in the energy sector

Include social and environmental clauses in public procurement contracts, at the selection, assessment and implementation stages, with the ultimate aim being to include social and environmental considerations throughout the energy procurement cycle. Launch processes to switch municipal electricity contracts to social, democratic and renewable energy enterprises that are publicly or cooperatively owned.

Participation | Proposal B.6: Public-community governance of public enterprises (energy retailers, energy services companies and energy demand aggregators)

Set up a space for public-community governance of public energy enterprises (retailers, energy services companies, potential municipal aggregators, etc.) to turn them into spaces in which energy governance is genuinely democratised. This public-community governance space should be obligatory and inclusive, enduring beyond electoral cycles so that it is possible to develop and implement long-term energy policies. It should also improve the overall quality of participatory processes so that municipalities and communities become increasingly empowered to strengthen the decision-making powers of all the community members and especially those more vulnerable residents.

Ecofeminism | Proposal C.7: Ensure an ecosocial and ecofeminist assessment of energy uses and sources to promote a new social metabolism in municipalities

Carry out or further develop a municipal-level energy assessment, so that these assessments are participatory. These assessments should include information about the sources of the energy used across the municipality and what it is used for, paying particular attention to reproductive and community uses. The assessment should lead to an ecosocial and ecofeminist energy covenant that includes a proposal on municipal energy planning focusing on the promotion of a new social metabolism, meaning that the flows of materials and energy that take place in the municipality are life-sustaining.

Ecofeminism | Proposal C.8: Organise public events using ecofeminist criteria

Make public events related to energy accessible to everyone, including those who need care and those who care for others (children, people dependent on carers, etc.) by, for example, making spaces suitable for children or dependent adults, providing interpreters and carers, etc.

Ecofeminism | Proposal C.9: Ensure data analysis includes disaggregation by gender and other intersecting inequalities

Develop tools for intersectional analyses that enable gender to be combined with other dimensions of inequality. Mainstream these analyses across energy-related data analysis processes. It is important for a common system of mainstreaming to be used across different municipal councils so that data can be easily compared.

Energy Generation | Proposal D.10: Facilitate medium-scale energy generation projects

Analyse available local government sites, such as municipal buildings and municipal land, where local renewable energy generation projects could be undertaken, and consider offering these sites to citizens’ groups who wish to take forward local renewable energy generation projects, under conditions to be agreed by both parties.

Seek advice to explore the potential for reaching a Public Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) with citizen funding and fair conditions that minimise future risks and benefit the public interest.

Energy Generation | Proposal D.11: Municipal bylaw on renewable energy installations

Ensure that urban planning regulations are accessible, understandable and provide clear information (in one place), about how to complete the required paperwork. Local level renewable energy installations often require complex paperwork or costly technical studies, which discourages their spread. A technical report and simple plans should be sufficient to issue a ‘statement of responsibility’ in order to encourage, instead of impede, small renewable energy installations.

Energy Distribution | Proposal E.12: Citizen audits of electricity distribution

Auditing of the electricity distribution grid and business is understood as the work required to obtain information about what electricity distribution was like in the past, how it is in the present and what actions should be undertaken in the future to ensure that it starts to prioritise the needs of residents.

Energy Retailing | Proposal F.13: Set up public electricity retailers

Promote the setting up of a publicly owned electricity retailer guaranteed to use renewable energy sources, with public-community participation in its governance process.

Energy Data Ownership | Proposal G.14: Taking steps towards energy data control: energy resource audits

Undertake full energy resource audits to quantify the multiple energy resources available to municipalities (for example, charging stations for electric vehicles, battery hubs, energy use in buildings or street lighting, self-generation, energy demand aggregation and renewable power plants). Proposals for improvement need to be developed in parallel in order to begin an energy transition focused on reducing energy use and, consequently, costs, as soon as possible.

Energy Data Ownership | Proposal G.15: Recovering data for digital democracy

Launch a local campaign and advocate for the ownership of data from energy meters, which is currently solely and poorly controlled by private distribution companies. Energy meters can provide instantaneous and hourly data, enabling the municipality to provide a demand aggregation service grid stability and balancing renewable energy production and demand. This would also reduce the unnecessary cost of having additional monitoring systems at public supply points.

Transport | Proposal H.16: Sustainable electric transport

Draw up plans for shared electric vehicle use to enable municipal electric vehicles to be used not only by local government employees during working hours, but by residents during evenings and weekends, paying particular attention to low-income groups.